Photography is part of my creative practice, my mental health support, my meditation. Here I reflect on the importance of this practice to me as a neurodivergent therapist.

Photography has been a part of my life since I was a kid, but it wasn’t til I did Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way back in my thirties that I realised its importance as play; a creative process I do for its own sake. Taking my camera off somewhere and immersing myself is something I’ve always done, as far back as I can remember. Later, I would discover my ability to stay still and notice the scenery was infinitely improved by the presence of a camera; without it, I’m likely to quickly jump up and move on, especially if I’m alone, thanks to my ADHD.

After completing two 8-week mindfulness practice courses in my early forties, as yet still undiagnosed, I felt a sense of failure that while I was perfectly able to meditate with others I simply could not do it alone. The irony is, mindfulness is very good for ADHD brains, but how do you get ADHD brains to be mindful? Body doubling–practice with others–is one thing a lot of ADHDers find supportive for making many things accessible, but I still needed some sort of daily practice I could do alone.

Then I realised walking meditation is part of many cultures’ spiritual traditions, including my own, and I started to re-imagine the ways in which I meditate. But how could I make walking mindful when my mind just tends to wander as I walk?

Enter, my camera (or these days, my camera-phone) as an accessibility aid. The camera slows down my thoughts, brings me into the here and now, gets me to notice what’s around me. Literally, it helps me focus. I have to breathe mindfully to steady my hand.

This morning, the day was grey and at first I just walked, full of thoughts about work and stress. I have fibromyalgia, among other health conditions, so my ability to walk varies day to day, week to week, and often I’m limited to shots from my mobility scooter in pavements and parks. But today the pain of a recent flare is easing off and my body told me gentle movement would help things improve.

Eventually I slowed down my thoughts and brought my surroundings into my awareness, looking for glimpses of colour, noticing the textures of the life and autumnal decay all around me. I think my autism, my monotropic brain, makes me notice detail, focus up close.

In the moment, it’s all about the process, but afterwards I also get the pleasure of sorting and sharing my photos–no filters, no AI, no staging, just a little glimpse of how Sam’s brain sees the world when it’s on slow mode.

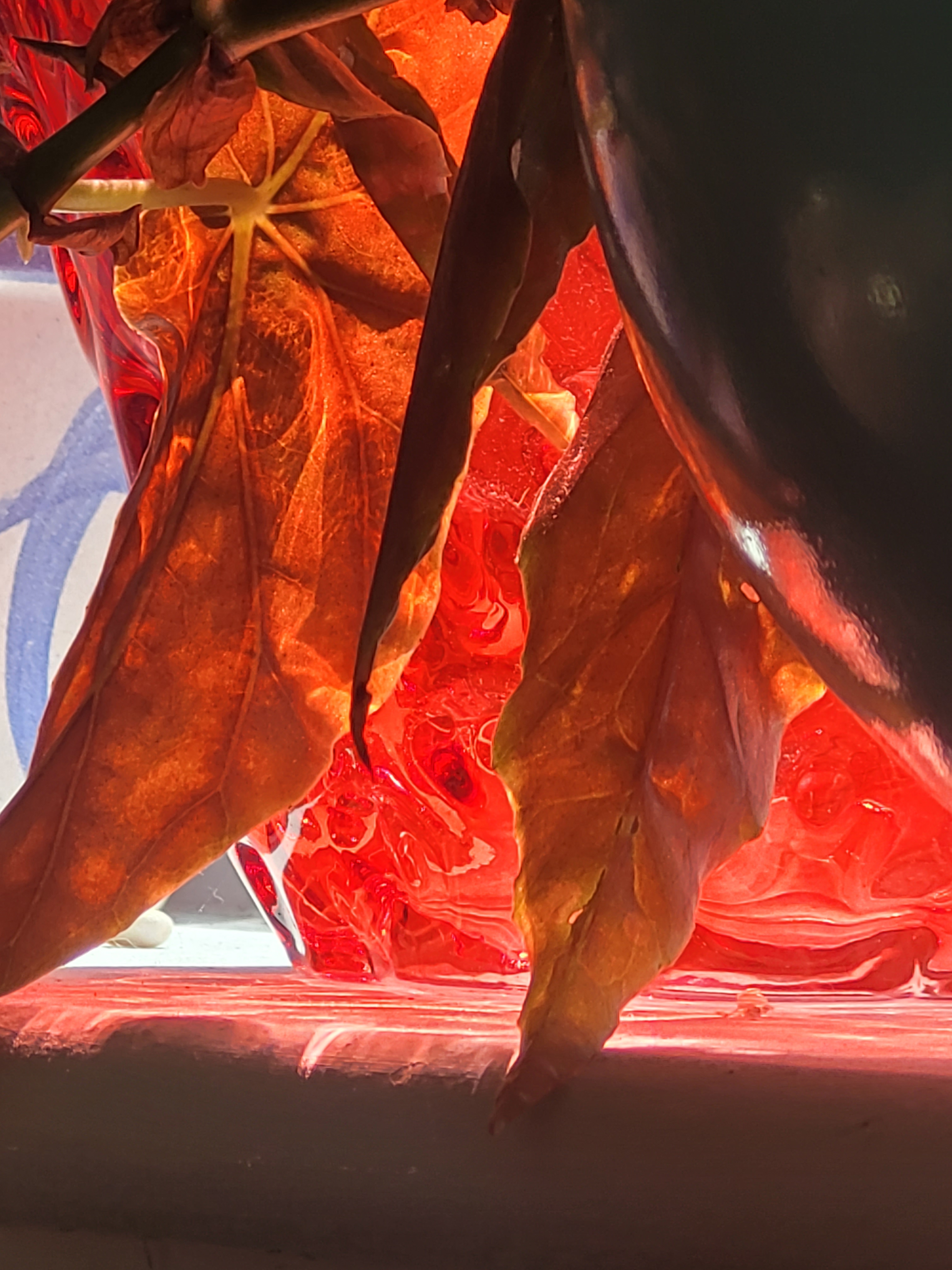

A few days ago I became transfixed by the evening sun shining through a wet, discarded sandwich wrapper:

Autumn this year naturally gave me plenty to feast my eyes on:

2025 hasn’t been an easy year. Being in the woods near my home hasn’t always been easy either, as constant reminders of the acceleration of climate change bombard my senses. But mindfulness isn’t just about distraction, it’s also about connection, and connecting down to my grief at this difficult moment in human history has been part of the work I do in the woods, even as I breathe in the beauty and give myself respite in the deliberately long spaces between client sessions.

This practice keeps me grounded in my commitments: To do the work, to play, to breathe, to rest, to stay connected, to slow down, to think deeper, and deeper still, to reflect more, to show up where I can, to refuse the rush, to commit to the long haul. And to never forget how beautiful the world is, even the broken bits.

Has my work helped your development this year? Please consider buying me a coffee to support my work as an independent, low-income disabled practitioner. Join my mailing list here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.